October 26, 2008

by Graham

56 Comments

This year has seen the centenary of the Spelling Society, formerly the Simplified Spelling Society, and inevitably there has been a lot of comment in the press, mostly uninformed criticism of anyone (particularly John Wells, as its President) who supports even a modicum of reform as an abandonment of “standards”.

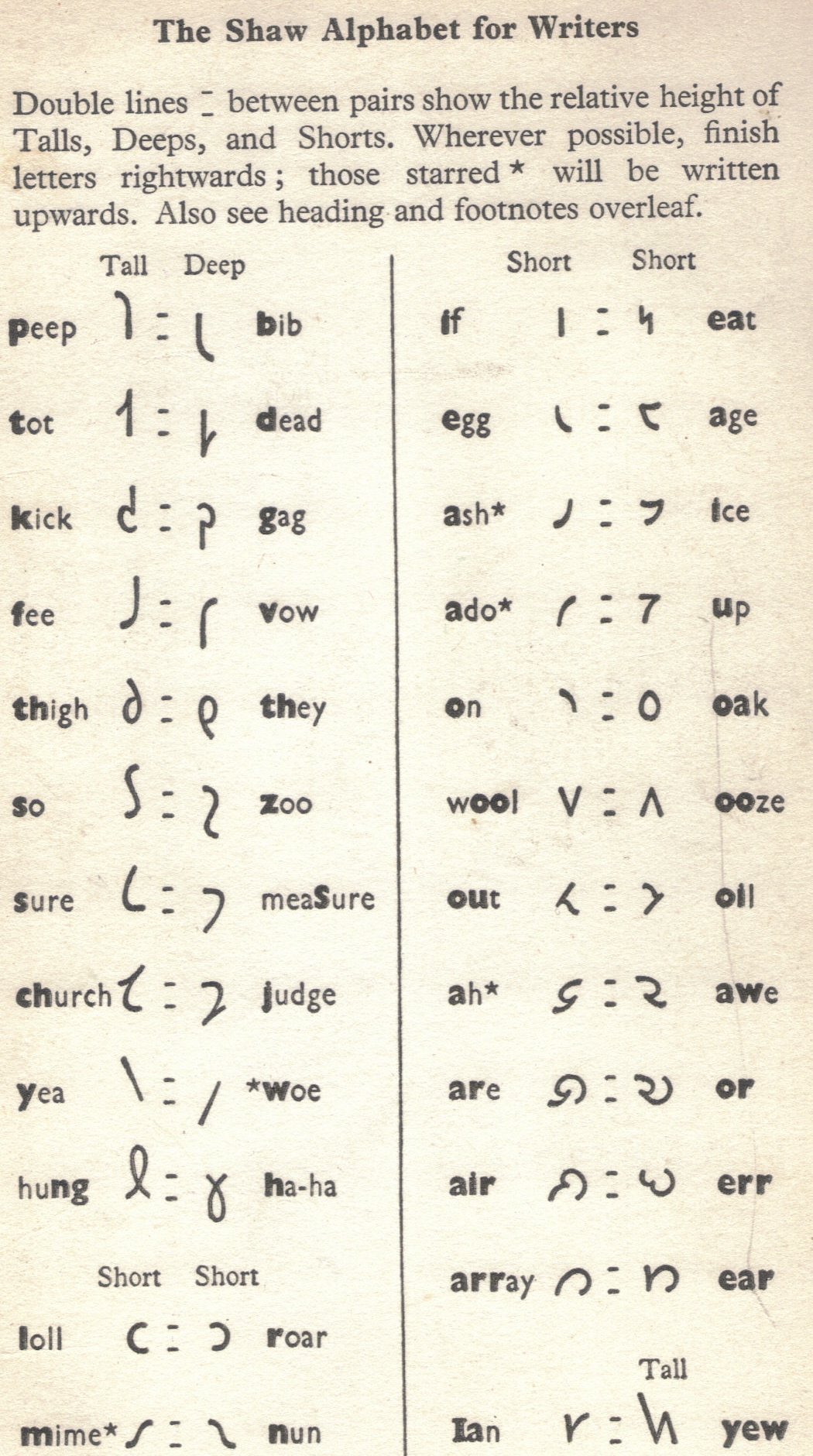

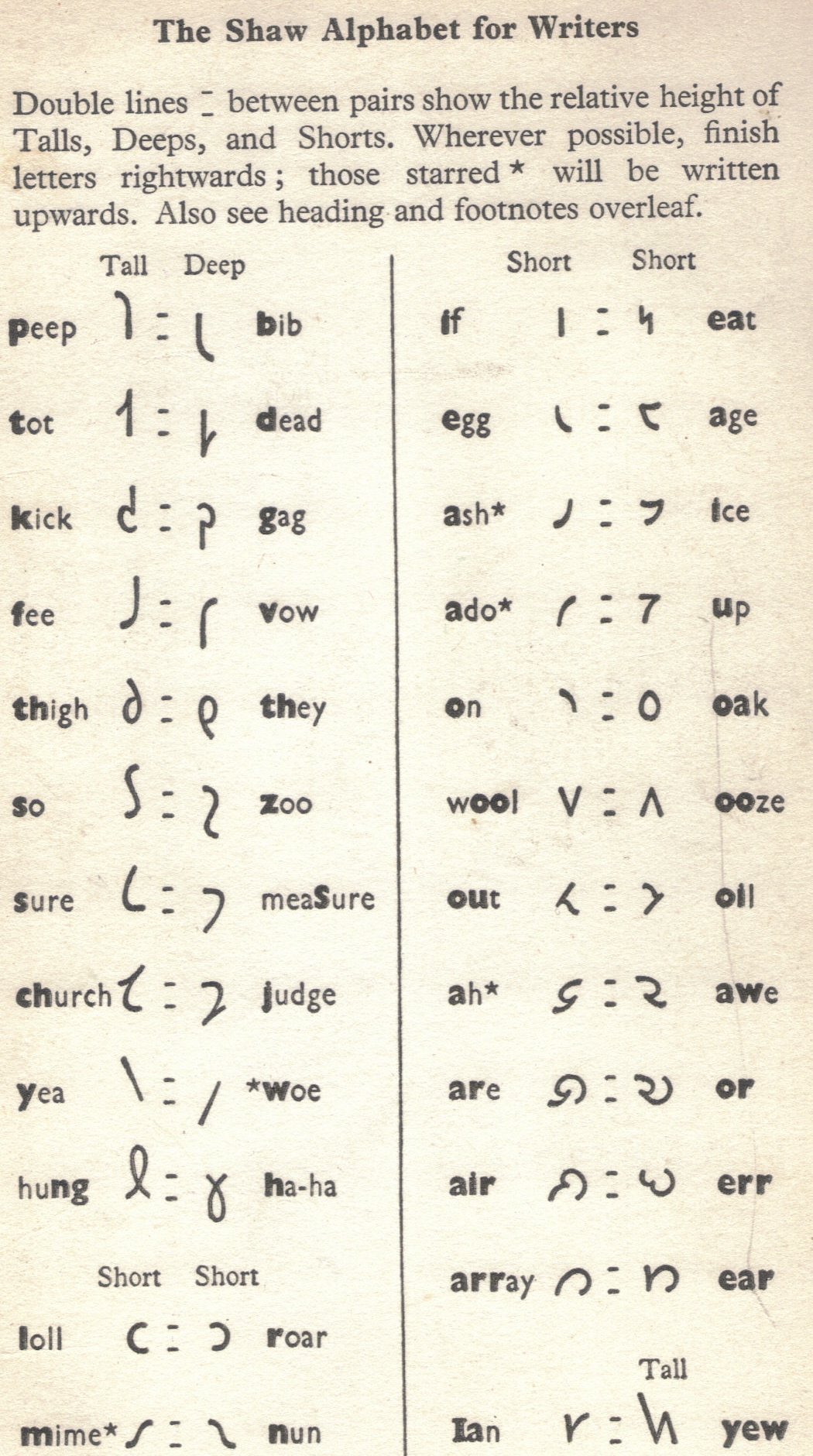

Proposals for reforming English spelling go back way before the Spelling Society was founded, but the momentum for change increased in the 20th century. Robert Bridges, as Poet Laureate, had enough clout to persuade Oxford University Press to reprint a series of his essays with ever increasing numbers of reforms, which included new or adapted letter shapes for particular sounds; Bernard Shaw went a step further, by leaving an immense amount of money in his will for the formulation of a new writing system for English, which would not be based on the Roman alphabet, and would not simply be a new form of shorthand. He wrote several letters to The Times on this subject in the 1930s and 1940s, using the economic argument that the only way of achieving success was to persuade politicians of the saving in terms of both money and time: an alphabet that contained a single symbol for each of the phonemes of English, thus obviating the necessity for digraphs and eliminating ambiguities (e.g. row, lead), would use up less space on the page, therefore less paper, therefore be cheaper; and quicker to both write and read, therefore saving much time, and therefore money. (The elimination of superfluous hard signs in Russian is said to have reduced the length of “War and Peace” by over 90 pages!)

Shaw’s will was overturned in the courts, but a competition to devise a new alphabet was held, and the winner was rewarded not only with a cash prize, but with the satisfaction of seeing his alphabet published by Penguin in a dual-text edition of “Androcles and the Lion” (1962). (One of the adjudicators, who also helped refine the winning entry, was Peter MacCarthy, who lectured in phonetics at several universities, and was my external examiner when I took the undergraduate course in phonetics at Edinburgh in the 1960s.) Right enough, this alphabet did save space – roughly one third of the page containing the Shaw alphabet version is blank, but there was no way that it could ever become a success: the Roman alphabet has now more-or-less conquered the world, and to expect anyone, native speaker or, perhaps especially, foreign learner to take the trouble to learn this new writing system is beyond belief.

Some simple reforms would be easy: the initial w and k of words such as wrong or knife could be dropped with no problem: they are pronounced in no variety of English that I have ever heard (an exception is the word acknowledge, where the /k/ is carried over from knowledge with the Latin prefix AD > AC by assimilation). This would be parallel to the change from Old to Middle English, when initial h of such words as hnutu (“nut”) stopped being written as well as pronounced. Most changes, however, would founder on arguments about which variety was to be the basis of the new spelling. The most obvious division is between rhotic and non-rhotic accents, but there are many others, such as the non-distinction of the THOUGHT and CLOTH vowels in Scots (Knots and Crosses is the punning title of Ian Rankin’s first Inspector Rebus novel), or the different distribution of the GOOSE and FOOT vowels in both Scots and Northern English, or, in Northern England, the lack of a split between STRUT and FOOT, which rhyme in many varieties. If each variety’s speakers were allowed to develop their own version of English spelling, life would be made very difficult for publishers!

It is noticeable that almost all the advocates of spelling reform use traditional orthography in their own writings (Jack Windsor Lewis is an exception in his blog, but not elsewhere). This is presumably because they do not wish to risk the anger of the general public, or politicians (such as David Cameron who attacked John Wells in a speech recently), who do not understand the arguments.

English is not the only language to have a difficult spelling system: French is notoriously difficult, and even Spanish, as I have written here before, is not totally transparent. Reform is possible – Norwegian, for instance, has undergone several spelling reforms since the late nineteenth century, mainly aimed at reducing its similarity to Danish. However, it is the ingrained attitude of the English-speaking public that will have to be changed before any progress can be made in simplifying the world’s premier language.